3d Art That Tricks the Eye Easy 3d Art That Tricks the Eye

Viii of the most mind-bending optical illusions in art

Tilt the painting one way and it is a vibrant heap of autumnal bounty, as apples, pears, grapes, and figs puzzle for position in an alluring, if seemingly conventional, withal life. Flip the oil-on-panel work on its head, as if shaking loose the fruit that fills the wicker handbasket, and suddenly the plumped-upward portrait of a stranger assembles itself from the bright jumble of assorted sweetness. The fibrous lashes of his anecdote eye wink at you playfully to punctuate the visual joke. Painted by the 16th Century Milanese Mannerist Giuseppe Arcimboldo, who would later inspire the imaginations of 20th Century Surrealist painters, Reversible Head With Basket of Fruit tricks the center into the restless practise of constructing and destroying 1 image in favour of the other. The issue is a work that is at once amusing and profound – ane that reminds the observer not just of the perishability of life but how our physical being is comprised, materially, of the fragile world around us. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

To stand in the middle of the medieval bridal chamber of the Ducal Palace in Mantua and look upward is to run into the enclosed space magically widen to a higher place you lot. Of a sudden, a shaft of unalterably cute blueish heaven beckons through a round discontinuity (or oculus) rimmed with angelic figures. Impossibly, the barrier of the ceiling appears to have dissolved, revealing an invisible architecture that telescopes towards sky, thrusting your soul in the direction of the divine. The evaporative effect is the handiwork of Italian artist Andrea Mantegna – a genius of dramatic foreshortened perspective and depicting figures illusionistically di sotto in sù (or "below upwards"). Mantegna saw the flat surface of a canvas or ceiling as an opportunity to take an observer's center and soul on a spiritual journey inwards, upwards, and outwards. Believed to be the showtime creative person since artifact to employ such an illusion as a dimension of interior pattern, Mantegna breathed new religious life into a heathen trick. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

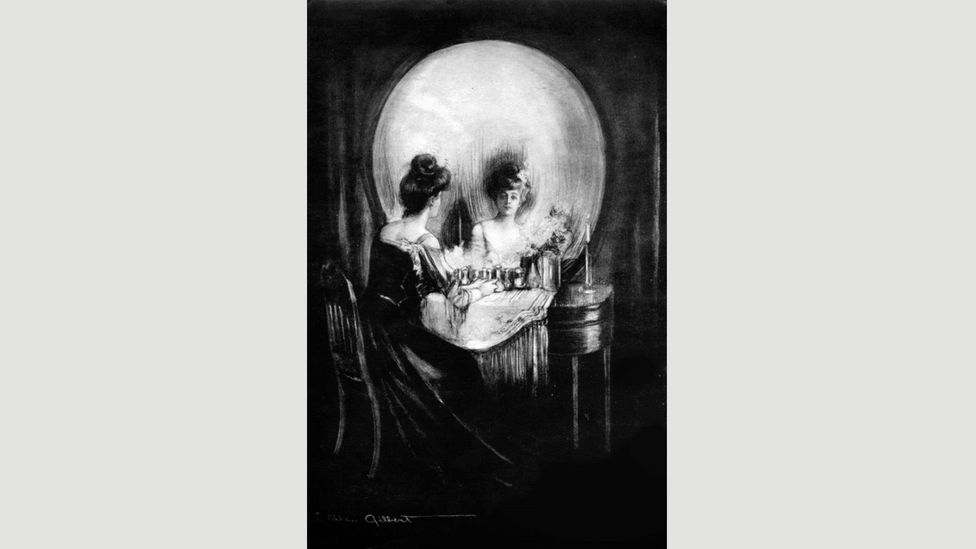

Stand up close to the black-and-white drawing and it appears to be little more a delineation of a familiar domestic interior scene: a adult female sitting at her dressing table (or "vanity") staring at her reflection in the mirror opposite. Step back, and the prototype, deprived of its scrutinisable details, curdles grimly into an all-encompassing skull, grinning gothically from the shadows. Once the 2 overlapping images are registered in the observer'south mind, the eye shuttles between comprehension of one and then the other, as they wrestle for priority. A contrivance of the illustrator Charles Allan Gilbert, the drawing offered American magazine readers in the endmost years of the 19th Century a fresh and startling spin on the convention of the memento mori (or 'remember you will die') in fine art history, which typically took the course of a skull inserted somewhere in a painting to remind viewers of their mortality. Seen from a 21st Century perspective, the inherent preachiness of the drawing (which visually puns on the scriptural admonishment "Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities; all is vanity") seems more than a little misogynistic in its emphasis on feminine narcissism as the chief locus of damnable frivolity and vice. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

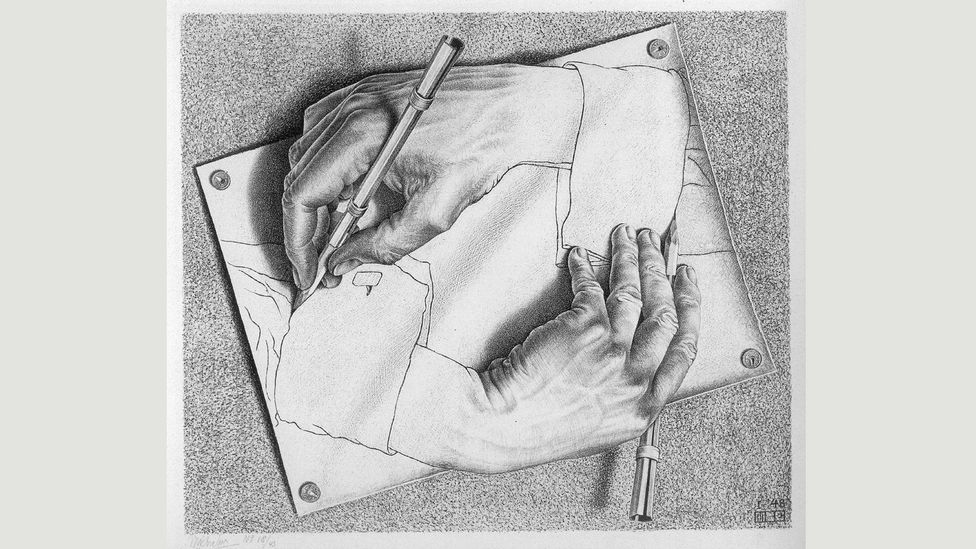

Used effectively, an optical illusion momentarily forces the observer to rethink the relationship between the real world that he or she inhabits and the one depicted in the work. No i understood the penetrative ability of illusion better than the Dutch graphic artist MC Escher. In his mesmerisingly meta Drawing Hands (1948), Escher magics from the work's sketchy surface a airtight-circuitry of the-hand-creating-the-paw-creating which appear to defy the limitations of 2-dimensional drawing. Obsessed with the mathematics of repeating patterns, Escher'due south piece of work was admired by leading contemporary physicists and philosophers. In Cartoon Hands, the graphite point of the mirroring pencil appears to be the teensy conduit through which the artist's beingness simultaneously flows into being and dissolves into nothingness. Defenseless in Escher'due south endless rotation, the viewer'due south eye is left to run circles around itself. (Credit: public domain)

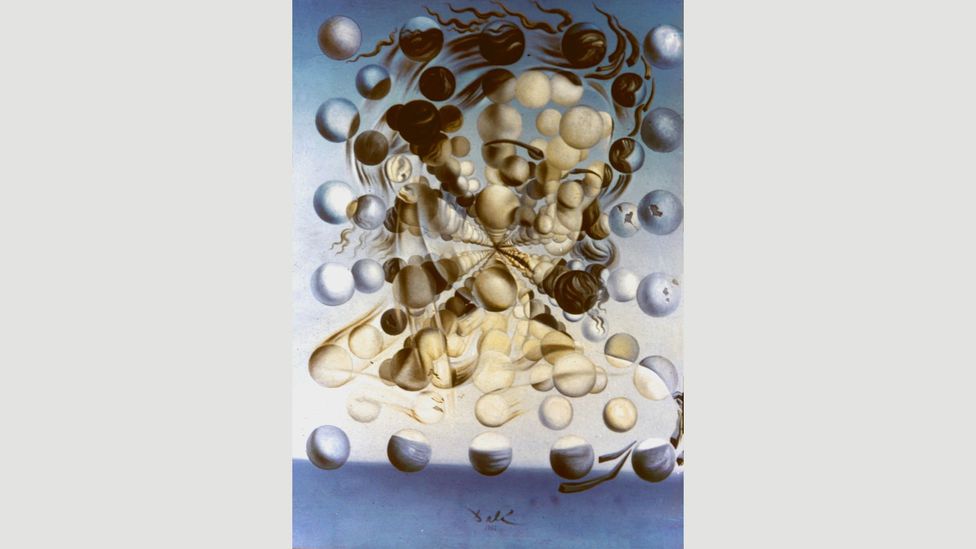

At first glance, the dynamic painting appears to capture the outward propulsion, towards the viewer, of countless colourful atoms – as if suspending in mid-blast a nuclear explosion occurring over a watery surface area. Zoom out, and the seemingly lawless blitz of spheres cohere loosely into the coy countenance of a adult female'south bosom, her caput tilted gently in a way that recalls countless Renaissance madonnas. Castilian surrealist Salvador Dalí'southward Galatea of the Spheres was undertaken at a moment of intense global anxiety at the prospect of nuclear armageddon and reveals Dalí's own accelerating preoccupation with atomic theory in the years post-obit the The states nuclear attacks on Japan in 1945. The creative person'south married woman, Gala Dalí, inspired the endlessly decomposing and composing portrait. By embellishing Gala's proper noun into an echo of the mythological sea-nymph Galatea of Ovid's Metamorphoses, Dalí has constructed an elastic work that simultaneously pulls together themes of antiquity and particle physics and blows them to smithereens. (Credit: Alamy Stock Photo)

Not every optical illusion in the history of art is remembered with fondness. One of the nigh hypnotic, if popularly dismissed, attempts to transfix the observer's eye was created by the pioneering French artist Marcel Duchamp, whose famous sideways urinal Fountain (1917) acquired a far bigger splash. Comprised simply of cardboard discs onto which the artist painted psychedelic spirals, the kinetic works spin into activity when placed, like vinyl records, onto a rotating gramophone-like gizmo. Nevertheless forcefully Duchamp's Rotoreliefs might have pulled the viewer's gaze into their stupefying whirl, the Dadaist'southward plan to make the discs a commercial success by selling hundreds of sets was a boundless disaster. Largely forgotten by anthologists of 20th-Century art, the Rotorelief's ambition to create a vertiginous experience for the observer by creating an eerily irresistible sensation of 3D depth on an abstract surface would non be resuscitated for another generation. (Credit: public domain)

If Géricault'due south Raft of the Medusa has the ability to brand observers nauseated in the face of so much heartbreaking inhumanity, British artist Bridget Riley'south Cataract 3 has the ability to make viewers woozy merely by opening their eyes. A deceptively simple work, consisting of wave upon wave of seasick-inducing lines, the hallucinatory canvas messes with one's equilibrium. A key player in the so-chosen Op Fine art (a contraction of 'Optical Art') movement that emerged in the 1960s, Riley was fascinated from an early on age with the optical techniques of Seurat and the pointillists – image theories that suggest a work's issue is finally completed in the listen of the viewer. Where pointillists relied on the viewer's mind to mix a blizzard of individual dots into colour and class, Riley seized instead upon the emotive power of minimalist geometric shape and black-and-white forms. The result is works of disorientating elegance that wrinkle the mind. (Credit: Bertrand Guay/AFP/Getty Images)

Since the early 1990s, the British graffiti artist Banksy has sought to lift the veil on social hypocrisies. In his famous landscape Sweeping it Under the Carpet, discovered in Chalk Farm, London, a hotel maid looks effectually sheepishly as she surreptitiously discards a dustpan-full of sweepings. But rather than lifting a carpet, she raises instead what appears to be the membrane separating the realm of urban art (in which she exists) from the real world that sprawls behind it. Though some recent forensic investigations into Banksy'due south real-earth identity accept sought to unmask the camera-shy street creative person, he has largely remained out of public view. Hidden under a hoodie of anonymising darkness, Banksy would rather be the wizard who manipulates our vision from backside the pall. (Credit: Jim Dyson/Getty Images)

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160518-eight-of-the-greatest-optical-illusions-in-art